I took an Uber to the train station without any issues, but it turned out to be the Mahattfat Misr station—not the Alexandria station I had arrived at a few days earlier. Like every train station I’d encountered in Egypt so far, this one had four ticket counters for different types of passengers and tickets.

That’s when things went sideways.

I got in the first line I saw, but it was long and painfully slow. Every customer seemed to be in a drawn-out conversation with the attendant, and language didn’t appear to be the problem.

I pulled out my go-to translation app that had worked flawlessly since I arrived. NO SERVICE. I tried again and again as the line slowly moved forward. STILL NOTHING.

With only one passenger left ahead of me, I Knew this was going to be a shit show.

Standing behind me was a very good-looking young man. One thing I’ve learned from international travel: if you’re looking for someone who speaks English, find the youngest person you can.

“Do you speak English?” I asked him.

“Yes,” he replied.

I explained my situation, and he offered to help. He spoke to the man behind the counter, who pointed to his right. As I started to walk that way, the young man said, “I’ll go with you.” He bought two tickets—for himself and his father, who was joining him—and we walked over to the other counter together.

Another long, slow line! When we finally reached the attendant, my new friend spoke with him for quite some time. Eventually, the attendant pointed us upstairs. I insisted I could take it from there, but he wouldn’t budge.

We gathered his elderly father, and the three of us headed to the elevator—stairs were too difficult for his dad. At the next level, we joined a third line, also long and slow. When we finally got to the counter, he went back and forth with the attendant in rapid conversation. It was clear that if I’d tried to navigate all of this on my own—especially without a translation app—it would’ve been a nightmare.

Finally, he turned to me and said, “$35 USD.” I slid the cash under the counter, and my ticket was issued. We compared our tickets and were amazed to see we were seated next to each other on the train!

We headed back down to the track level with his father, and I found myself genuinely impressed by this young man.

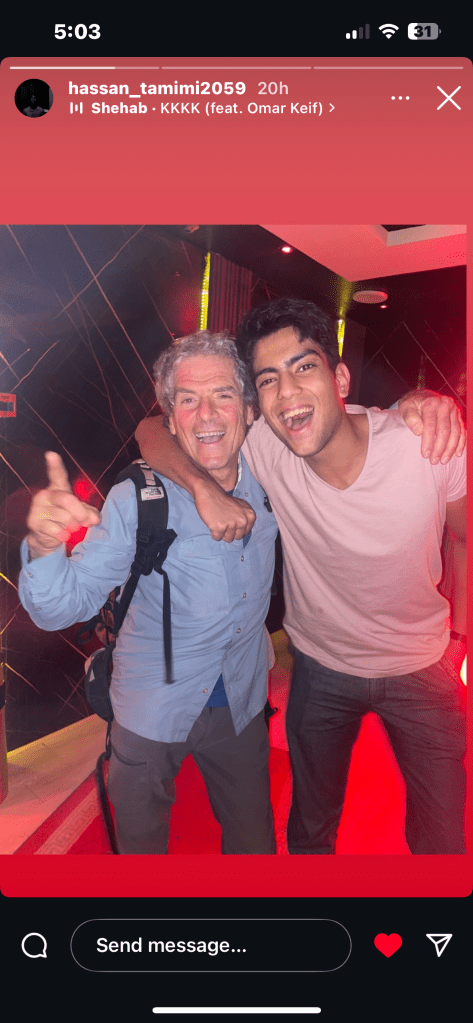

His name was Mohammed, but he went by Hassan, and he was 19 years old. We talked about everything—sports, politics, careers, women, movies, health, music, family, even drugs. He explained that he was regularly tested on his English comprehension and was currently at a B2 level. He hoped to reach B1 soon, and I was more than happy to help him just by having a great conversation. His knowledge of American politics certainly exceeded almost any 19-year-old American.

We boarded the train and the conversation went on. He then asked me if I would join him in the cigarette car. I did so, and he translated with me in conversations with various people in that car. As asphyxiating as the smoking car was, I was more than happy to put up with it because I was learning much more about Egyptian culture than I had the previous nine days.

I found out that he and his dad loved to smoke cigars. I brought 3 on my trip and only smoked one. Having 2 Big cigars left a Flat Head Churchill and their biggest, a huge V770 Big Block, I gave them to Hassan and his dad for which they were very grateful.

At the train station (Mahattfat Misr), things got complicated. My translation app lost service, and the lines were long and slow. A young man nearby, Hassan, offered to help. He spoke English well and guided me through multiple counters, buying tickets for himself and his father.

We ended up seated next to each other on the train. Hassan, 19, spoke about many topics and was eager to improve his English. He invited me to the smoking car, where I learned more about Egyptian culture despite the thick smoke.

I gifted Hassan and his dad two of my remaining cigars, which they appreciated greatly.

Most striking was that most of the things that I had always thought were taboo in the Muslim world were Also done here in Egypt. Maybe not as openly, or frequently, or commonly as Americans do, but in so many ways, we are ever so similar!

Our train ride was three hours and I then had five hours before my flight, but I was still a half hour drive from the airport. Hassan asked me if I would join him for a drink and I said “but you’re only 19“. He said “that’s OK. I’ll tell them that I am your guide!”

I agreed, and when we left the train station, his father aggressively negotiated with about six cabdrivers till he finally got his price. We took the cab to their apartment, unloaded their luggage, and I had a chance to chat with his dad while Hassan was getting ready to go out. His dad told me that he used to speak English fluently but hadn’t been doing so for 25 years so he had largely lost it. Turns out that while he was quite elderly, he was a year younger than me. We were ready to leave and his dad told me that next time I come to Egypt, with or without my wife, I would be welcome to stay there. His dad then contacted a friend to drive us to where we wanted to go.

We got in the car, and Hassan called out, “Richie! Where do you want to go!?” I said, “Well, I’m in Egypt—I want to see a belly dancer.” Turns out belly dancers in Egypt are no longer “a thing”.

What struck me most was how many things I thought were taboo in the Muslim world happen in Egypt—maybe less openly or often than in the U.S., but we’re surprisingly similar.

Our three-hour train ride ended with five hours before my flight, but I was still 30 minutes from the airport. Hassan invited me for a drink. I hesitated since he was only 19, but he said he’d say he was my guide, so I agreed.

At the train station, his dad negotiated with cab drivers before we headed to their apartment. I chatted with his dad, who once spoke fluent English but hadn’t used it for 25 years. Surprisingly, he was only a year younger than me. He warmly invited me to stay next time I visit Egypt.

Later, Hassan’s dad arranged a ride for us. Hassan asked where I wanted to go. I joked about seeing a belly dancer, only to learn belly dancing isn’t really a thing in Egypt anymore.

They exchanged looks, unsure about my idea but clearly wanting to entertain their new American friend. Hassan started working his phone and chatting with the driver—though in Egypt, “chatting” often sounds more like a heated argument.

They looked at each other, contemplating our options. They expressed some doubt about my idea—they weren’t sure where to go—but they were eager to do whatever they could to entertain their new American friend.

Sure enough, Hassan started tinkering with his phone and began chatting with our driver, who was much older than him. I’ve come to learn that “chatting” among Egyptians often sounds more like a knock-down, drag-out argument. After weaving through a few side streets, we pulled up in front of what appeared to be a very exclusive place.

We went inside and were greeted warmly. The men working there were all in tuxedos, and we could hear a band playing loudly as we climbed the stairs.

Sure enough, a belly dancer was performing—and she exceeded all my expectations.

After weaving through narrow side streets, we pulled up to what looked like a very exclusive venue. Inside, we were warmly greeted by men in tuxedos, and a live band echoed up the staircase.

Sure enough, a belly dancer was performing—and she exceeded all my expectations.

We were served three trays of fruit and vegetables and two Heinekens each. As we worked through about half of each plate, well-dressed staff swarmed our table. They kept refilling our beers and replacing any half-eaten dish with a fresh one, without missing a beat.

I handed Hassan a $100 bill to let him know I wanted to cover everything. My flight was at 4 a.m., and the driver said we could leave around 2. I wasn’t too comfortable with that timeline, so when 1 o’clock rolled around, I stood up and told Hassan and the driver it was time for me to go. I ordered an Uber.

We walked outside to a quiet spot, and I asked Hassan to find out the final bill. He checked and said it would be another $40, so I handed over the cash and made my way downstairs—my Uber was already waiting.

I arrived at the airport without incident with plenty of time for my 4AM flight.

We were served three trays of fruit and vegetables and two Heinekens each. As we casually worked through the plates, sharply dressed staff buzzed around us with near-military precision—refilling our beers, replacing any half-eaten dishes with fresh ones before we even had a chance to notice.

Wanting to cover the evening, I handed Hassan a $100 bill. My flight was at 4 a.m., and while the driver said we could leave by 2, that felt too tight for comfort. So, when 1 o’clock rolled around, I stood up and told them it was time for me to head out. I ordered an Uber.

Outside, we found a quiet spot and I asked Hassan to check on the final tab. He came back and said it was another $40, which I gladly handed over. My Uber had already arrived downstairs.

I arrived at the airport smoothly and with plenty of time to spare for my 4 a.m. flight.

THANK YOU FOR VIEWING:

www.richcitroadventures.com/egypt. You will note that 4 other adventures are available on the site and I can assure you that they are every bit as entertaining!

If you are planning to visit any of these places these episodes are a Must See!